A leap forward in AI ethics and safety

July 5, 2024

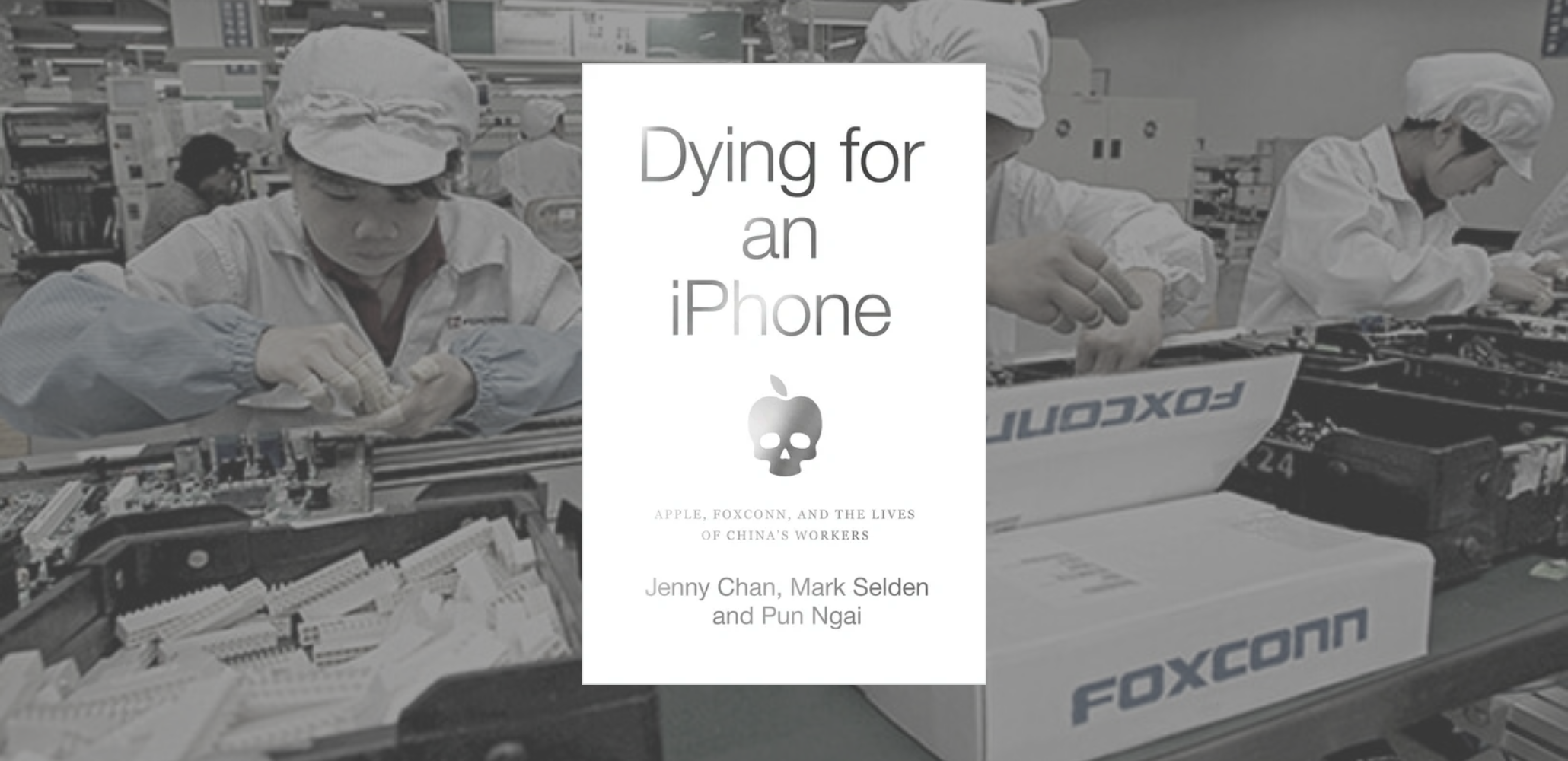

Suicides, excessive overtime, and hostility and violence on the factory floor in China. Drawing on vivid testimonies from rural migrant workers, student interns, managers and trade union staff, Dying for an iPhone is a devastating expose allowing us to assess the impact of global capitalism’s deepening crisis on workers. Interview with co-author Mark Selden.

Hi Mark, so why did you write this book… now?

Mark Selden: One important stimulus for my collaboration with Jenny Chan and colleagues was the suicides of eighteen Chinese rural migrant workers at the Foxconn factories in China in 2010, calling into question the pristine image of both Foxconn and Apple in making our iPhones, and, indeed, Chinese and American capital in the new global economy.

Foxconn, a Taiwanese multinational corporation founded in 1974, had risen to become the largest electronics employer with more than 1,000,000 workers in China alone at its peak in the 2010s. Before the spate of suicides, the company had been designated as the sole contract manufacturer of iPhones, the signature electronic product of the era. To this day, amid the de-risking talks of “China Plus One” among corporate leaders, Foxconn’s largest production base remains China.

“Designed by Apple in California” and “assembled by Foxconn in China” sets the historical background and social context of my coauthored book, Dying for an iPhone: Apple, Foxconn, and the Lives of China’s Workers, published by London-based Pluto Press and Chicago-based Haymarket Books in 2020, and translated into Korean by Seoul-based Narumbooks in 2021. The book won two awards from CHOICE for the Outstanding Academic Title on China (2022) and Outstanding Academic Title in Work and Labor (2022). Interested readers can browse the website at www.dyingforaniphone.com.

From a macro perspective, the US-China economic partnership had emerged in the 1970s, initially driven by a shared anti-Soviet alliance and deepened following China’s entry into the World Trade Organization.

Here’s an important fact: by 1978, when China re-opened its market, Chinese workers were earning approximately 3 percent of US wage levels. This is critical to understanding the massive transfer of US manufactures to China, initially textiles and shoes and later higher value-added electronics and automobiles. Within a few decades, China rose to become the world’s second largest economy, though its growth has slowed since the 2008 Global Financial Crisis.

In the 21st century, the rise of Apple to become one of the world’s most profitable tech companies (with US$59.5 billion in profits in 2018, that is, more than thirteen times greater than Foxconn’s in the same year), is a quintessential U.S.-China corporate story. I wondered whether Apple could maintain its corporate image in the face of the wave of suicides at Foxconn, producer of its most lucrative product?

Dying for an iPhone is a story emblematic of the new face of global capitalism and US-China competition for geopolitical and economic supremacy.

An extract from your book that best represents yourself?

M. S.: Let me share several translated Foxconn worker poems, from the original Chinese, with concerned readers, including Apple fans from all over the world.

Die by Suicide

To die is the only way to testify that we ever lived.

Perhaps for the Foxconn employees and employees like us,

the use of death is to testify that we were ever alive at all,

and that while we lived, we had only despair.

—A Chinese worker’s blog, May 27, 2010

(Source: Dying for an iPhone, p. ix)

On My Deathbed

I want to take another look at the ocean,

Behold the vastness of tears from half a lifetime

I want to climb another mountain,

Try to call back the soul that I’ve lost

I want to touch the sky,

Feel that blueness so light

But unable to do any of these,

I’m leaving this world.

Everyone who’s heard of me

Shouldn’t be surprised at my leaving

Even less should you sigh or grieve

I was fine when I came,

and fine when I left.

—XU Lizhi (1990-2014), a Foxconn rural migrant worker, September 30, 2014

(Source: Dying for an iPhone, p. 190)

For My Departed Brothers and Sisters

I’m like you

I was just like you:

A teenager leaving home

Eager to make my own way in the world

I was just like you:

My mind struggling in the rush of the assembly line

My body tied to the machine

Each day yearning to sleep

And yet desperately fighting for overtime

In the dormitory, I was just like you:

Everyone a stranger

Lining up, drawing water, brushing teeth

Rushing off to our different factories

Sometimes I think I’ll go home

But if I go home, what then?

I was just like you:

Constantly yelled at

My self-respect trampled mercilessly

Does life mean turning my youth and sweat into raw material?

Leaving my dreams empty, to collapse with a bang?

I was just like you:

Work hard, follow instructions and keep quiet

I was just like you:

My eyes, lonely and exhausted

My heart, agitated and desperate

I was just like you:

Entrapped in rules

In pain that makes me wish to end this life

Here’s the only difference:

In the end I escaped from the factory

And you died young in an alien land

In your determined bright red blood

Once more I see the image of myself

Pressed and squeezed so tightly I cannot move.

—YAN Jun, a female rural migrant worker

(Source: Dying for an iPhone, pp. 176-177)

The trends that are just emerging that you consider significant?

M. S.: The emergence of China as the world’s leading industrial and trading nation, and the shift from US support for China’s rise as the leading US trade and investment partner to attempts by both the Trump and Biden administrations to block China’s rise by denying access to US technology. This is underlined by the creation of multiple US-led regional-global alliances targeting China including US-Japan-India-South Korea as well as attempts to pressure the European Union/NATO to reduce trade and investment with China and to strengthen NATO’s military to target China.

If you had to give one piece of advice to a reader of this article, what would it be?

M. S.: It is time to overcome the long-held assumptions of corporate beneficence on both sides when dealing with the likes of Foxconn and Apple in China. The plights and struggles for betterment among Chinese workers in global supplier factories are my focus. Foxconn’s “union” with a million-strong “members” has been headed by the secretary of the Foxconn boss, that’s why workers’ trust in “their” union is very low. Moreover, Foxconn Union, not unlike any other enterprise unions, are subordinated to the government-controlled All-China Federation of Trade Unions (ACFTU), the only official trade union organization in China. In brief, the multiple suicides of Foxconn workers were a spectacular example of labor problems that were addressed by Foxconn essentially by erecting safety nets outside its dormitories, while fundamental labor rights centered on the low wages and compulsory overtime of rural migrants in China’s regime of state capitalist accumulation deserve great attention.

The fact is that hundreds of millions of rural migrants and their children are denied equal citizenship, welfare and education rights in China’s cities. These migrants have been “urbanized as labor” but not recognized as “full human beings” whose social reproduction, health and welfare is grossly neglected by both the government and employers.

In a nutshell, what are the next topics that you will be passionate about?

M. S.: My latest book, A Chinese Rebel Beyond the Great Wall: The Cultural Revolution and Ethnic Pogrom in Inner Mongolia, coauthored with TJ Cheng and Uradyn E. Bulag, was recently published by the University of Chicago Press. It has taken me to the terrain of China’s treatment of its minority nationalities, in this case the Mongols, but also, particularly to Uyghurs of Xinjiang and the Tibetans. These are issues that resonate with issues of American migrants and American minorities including Indians, Black, Latinos and Asians.

Concerning informalization and digitalization, the new frontier in labor strife centers on workers in the platform economy including ride-hailing drivers and food and parcel deliverers, many of whom have no formal employment contract and are subject to the whims of big Chinese and global capital. Indeed, the platform economy is at the center of labor conflict in the US, China and many other countries.

Thanks Mark Selden

Thank you Bertrand Jouvenot

Biography

Mark Selden taught historical sociology at the State University of New York at Binghamton (retired) and is the founding editor of The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, a peer-reviewed online publication providing critical analysis of Japan, China, Korea and the Asia-Pacific. He is the editor of book series at Rowman & Littlefield and Routledge publishers. He is the author or editor of thirty books including Chinese Village, Socialist State (with Edward Friedman and Paul G. Pickowicz); Chinese Society: Change, Conflict and Resistance (co-edited with Elizabeth J. Perry); Dying for an iPhone: Apple, Foxconn, and the Lives of China’s Workers (with Jenny Chan and Pun Ngai), and A Chinese Rebel Beyond the Great Wall: The Cultural Revolution and Ethnic Pogrom in Inner Mongolia (with TJ Cheng and Uradyn E. Bulag), among others. https://markselden.info/

Mark Selden taught historical sociology at the State University of New York at Binghamton (retired) and is the founding editor of The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, a peer-reviewed online publication providing critical analysis of Japan, China, Korea and the Asia-Pacific. He is the editor of book series at Rowman & Littlefield and Routledge publishers. He is the author or editor of thirty books including Chinese Village, Socialist State (with Edward Friedman and Paul G. Pickowicz); Chinese Society: Change, Conflict and Resistance (co-edited with Elizabeth J. Perry); Dying for an iPhone: Apple, Foxconn, and the Lives of China’s Workers (with Jenny Chan and Pun Ngai), and A Chinese Rebel Beyond the Great Wall: The Cultural Revolution and Ethnic Pogrom in Inner Mongolia (with TJ Cheng and Uradyn E. Bulag), among others. https://markselden.info/

The book: Dying for an iPhone, Mark Selden, Jenny Chan, Pun Ngai, Haymarket Books, 2020.